A Chinese scholar’s optimistic outlook oversimplifies the difficulty of repairing a dangerously frayed relationship

A People’s Republic of China (PRC) scholar’s recent commentary on US-China relations is refreshing in its even-handedness and optimism. The author of the July 5 essay, Wu Xinbo, is the dean of the Center for American Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai and has substantial experience exchanging views with US foreign affairs experts.

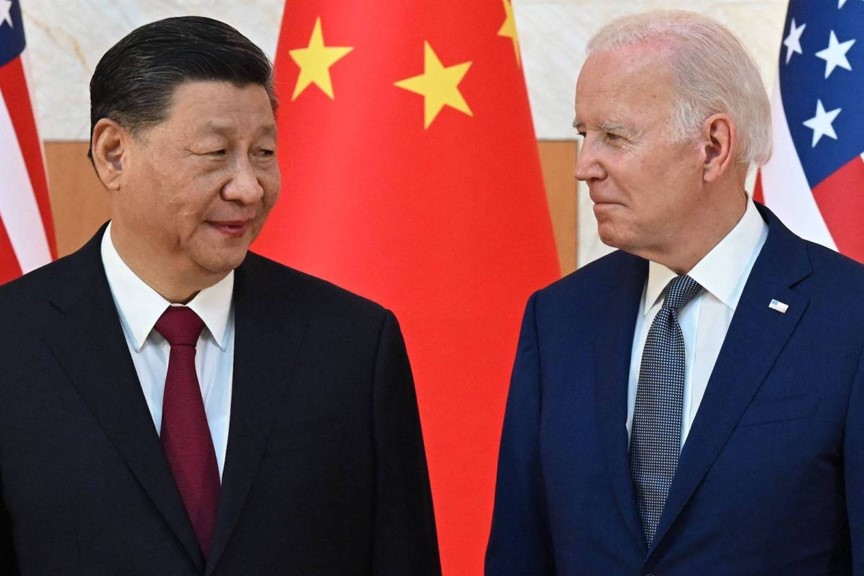

Nevertheless, Wu oversimplifies the difficulty of repairing this dangerously frayed bilateral relationship. Echoing what PRC officials have recently been saying, Wu argues that the 2022 meeting in Bali between PRC General Secretary Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden established a useful “foundation” for improved US-China relations.

Wu summarizes the commitments at the Bali meeting as follows: Xi said “China does not seek to change the existing international order or interfere in the internal affairs of the US, and has no intention to challenge or displace the US.” Wu paraphrases Biden as saying “the US respects China’s system, does not seek to change it and has no intention for a new Cold War.”

In practical terms, however, this foundation is so riven with cracks as to be nearly useless. From the US standpoint, Beijing’s insistence that Taiwan must become a province of the PRC, whether voluntarily or by military force, is an attempt to change the existing order.

And so are PRC claims to ownership of the South China Sea, PRC encroachment on the Sino-Indian border and PRC designs on Japan’s Ryukyu Islands. China’s attempts to interfere in the domestic politics of the US are well-documented.

Xi’s denial of an intent to “displace the US” as a global or regional leader similarly lacks credibility. PRC officials and media relentlessly attempt to de-legitimize US leadership by defaming the United States as warlike, declining, hypocritical and pushing allies toward disaster.

Beijing frequently threatens US partners with economic or military harm if they cooperate too closely with the Americans. On July 3, Politburo member and former foreign minister Wang Yi rather bizarrely told Japanese and South Korean diplomats they should side with China against the West because of common Asian racial ancestry.

Nor do Biden’s Bali commitments offer China much to build on.

A statement that the US government “respects China’s system [and] does not seek to change it” is an improvement over the Trump administration’s call for the international community to work toward the overthrow of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

But it does not mean Washington will cease publicly criticizing the CCP government for being “authoritarian” and for denying its subjects civil and political rights, criticism that enrages Beijing.

The Chinese might think that if America says it does not want a “new Cold War,” it logically follows that the US government will stop what Beijing alleges is supporting Taiwan’s independence and attempting to build an “Asian NATO.”

In Washington’s view, however, the way to achieve peace and stability is to strengthen the potential counter-China coalition enough to dissuade Beijing from attempting military adventurism.

In sum, Xi and Biden talked past each other at Bali, which explains why the bilateral relationship did not improve in the months afterward.

Academic Wu says China and the US should “draw red lines for both sides” and that “each does not pose an existential threat to the other.” The “red lines” idea is similar to the Biden administration’s “guardrails” metaphor.

By adding the additional phrase “existential threat,” however, Wu previews why this idea would fail.

The strategic flashpoints with the highest risk of US-China military conflict all involve cases of PRC expansionism mingled with irredentism: Taiwan, the South China Sea, the Sino-Indian border and the East China Sea.

Since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) government claims all of these areas as rightfully Chinese territory, the “loss” of any of them is by definition an existential threat to China.

Complying with Beijing’s red lines would require the US to abandon Taiwan and the South China Sea to PRC annexation. Washington is clearly unwilling to do that. The most the US side could do is restate that it is not actively encouraging Taiwanese independence, which the PRC side does not believe.

Meanwhile, politicians from both major US parties continue to use support for Taiwan as a means of virtue signaling, undercutting the White House’s assurances to the PRC.

Wu argues that “Washington has stressed too much competition” with China at the expense of cooperation. Instead, he says, “we should sit down to discuss what will be a realistic agenda for cooperation.”

Wu is certainly correct that despite the strategic tensions, there remains a broad array of areas where China and the US can and should cooperate for mutual benefit. There are, however, two problems here.

First, Beijing tends to hold important areas of potential cooperation hostage to unrelated bilateral disputes, requiring that Washington first make concessions before Beijing will agree to talk about making progress on an issue that is also in China’s interest. Examples are confidence-building measures and climate change. So the discussion on a “realistic agenda” would likely begin with some attempted extortion by the PRC delegation.

A second problem is that economic “de-risking” is not going away. The top “cooperation” priority for the PRC today is to regain the degree of access to US technology that China previously enjoyed. China, however, used that previous access to build up formidable military capabilities and demonstrated alarming intentions toward important US interests.

Now that China is a dangerous potential adversary, the bilateral relationship is permanently changed. US policymakers will increasingly forego cooperation that promises immediate economic rewards if the longer-term result would be increased US vulnerability.

The discussion that Wu envisions is unlikely to result in the US buying Huawei equipment or lifting the restrictions on PRC access to advanced semiconductors.

Washington would be open to talking about cooperating on climate change and avoiding accidental military incidents, but it’s unclear that is what Beijing really wants.

Finally, Wu calls for Sino-US negotiations on “some adjustments” to an “international order” that he says excessively caters to US preferences. In principle, this is reasonable. China is an emergent great power in a region already dominated by a long-established great power, a historically recurrent war-prone situation.

Accommodating China by changing the rules of international interaction is preferable to a decision by China that it must fight a war to replace US rules with Chinese rules. As with the “red lines” issue, however, it is doubtful that the “adjustments” the US is willing to make would satisfy Beijing.

Key sticking points would be China’s insistence on winning its territorial claims, Chinese opposition to US alliances and military activity in the region, and US opposition to PRC economic coercion.

Wu suggests a new order should be based on the United Nations Charter. But neither this nor any other legal document would be sufficient to smooth over the current frictions or adjudicate future disputes between the PRC and US.

Even now, Beijing argues that US military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan violated the UN Charter. Washington can point to the PRC’s human rights violations, disregard for the Law of the Sea and support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Great powers pursue their self-interests first, often in defiance of the rules, and then secondarily limit reputational damage as best they can.

Wu’s commentary graciously avoids the usual Chinese call for the US to “correct its mistakes.” Nor does it admit to any imperfection in PRC policies, which is typical of PRC-based analysts. This evasion makes possible a hopefulness that, unfortunately, is superficial and unrealistic, despite Wu’s apparently admirable intent.

Denny Roy is a senior fellow at the East-West Center.

Source: asiatimes