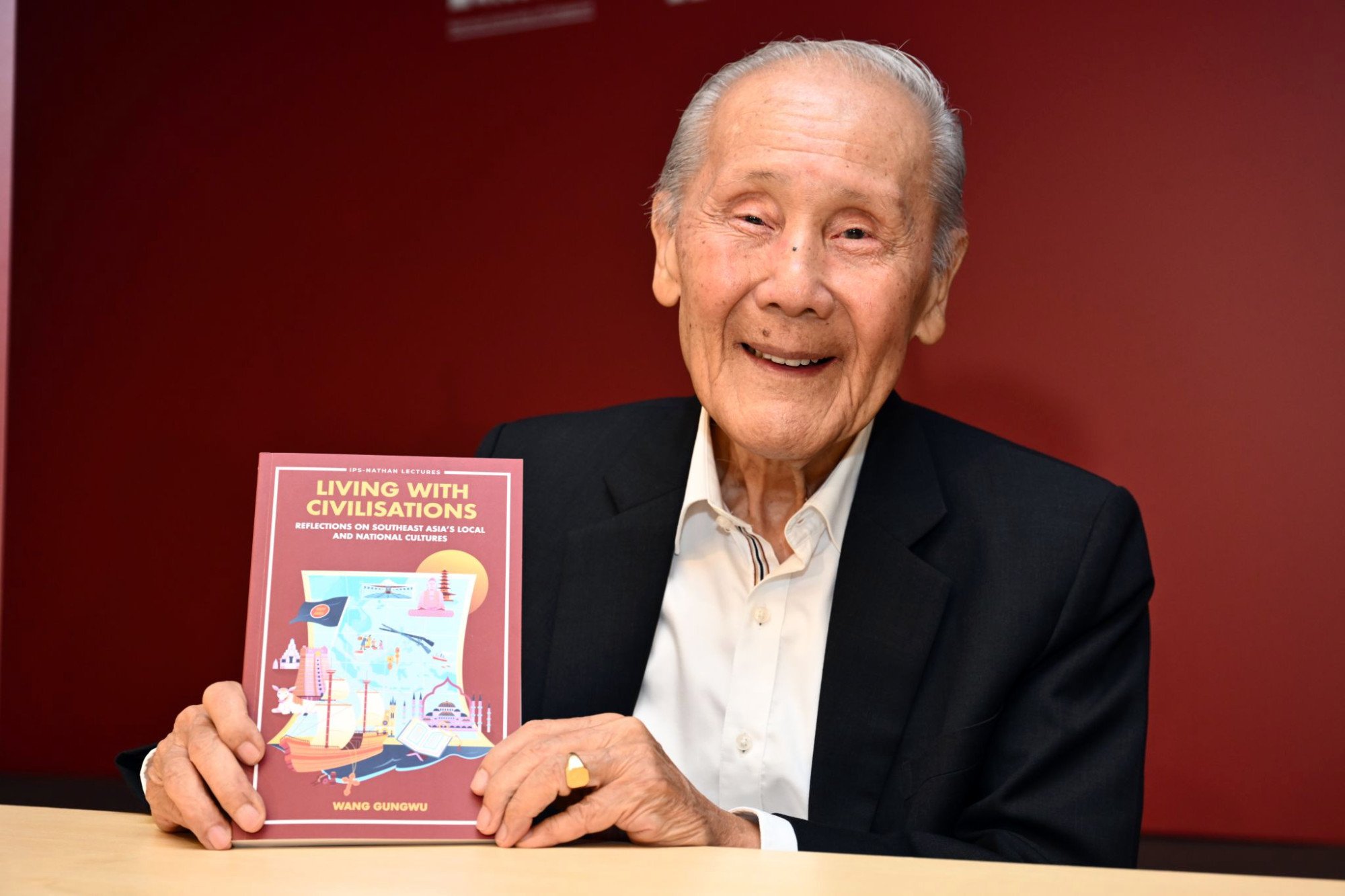

In Living With Civilisations, a recently published collection of four IPS-Nathan Lectures by Singapore-based professor Wang Gungwu, he explores the civilisations that shaped the history and nation-building process of Southeast Asian states. The following excerpt is from the prominent China historian’s fourth lecture, on Chinese-majority Singapore’s “exceptional conundrum” in balancing its ties with the United States and China.

Singapore tells an extraordinary story of adjustment and adaptation that is especially pertinent to the subject of these lectures. As an unexpected nation-state, its first leaders did well by their decision to embrace its modern administrative and legal heritage, and expand the range of its imperial economic connections. It saw the United Nations organisation as the embodiment of a renewed Enlightenment civilisation. This protected sovereign nation states wherever located and however small.

With this shield, the island-state was enabled to nation-build with a plural society that drew from several living civilisations. From a unique combination of policies and practices, the new state laid the foundations of a first-world nation at the heart of Southeast Asia.

Everyone was conscious that three-quarters of Singapore’s population was of Chinese origin. That had always been a source of unease in the region. Furthermore, no one foresaw the swift rise of China and its turn towards a state-centred capitalism that provided it with the economic power to make it appear as a threat to the United States.

Nobody anticipated that the severely weakened Sinic civilisation could have used its two revolutions to achieve modernisation so quickly. It now claimed to be the successor to a continuous Sinic centralised state. When China also claimed to have drawn inspiration from the same Enlightenment roots as the West, the US began to demonise the Communist Party-led party-state as returning to the ideology previously represented by the Soviet Union. This ignores China’s deep roots in a civilisation that had considered itself central and exceptional for millennia.

China’s success in using the developed world’s free-market economy to reach out to the developing world has made its modern claims more credible than anyone thought possible. Equally surprising has been the American response. Politically polarised by extremists of every colour and creed, the US has called for an aggressive nationalism against China. That seemed to have been the only call that could unite the country.

In response, China has revived the nationalism that had enabled its people to resist Japanese invasions a century earlier. What is new is that both China and the US now see themselves as representatives of progressive civilisations. The US, as guardian of the liberal Enlightenment, has portrayed China as a throwback to the failed ideology of communism. It has now asked for its military allies in Nato to move further east to help end the threat of a rerun. Together, they hope to restore the liberal dominance that had triumphantly won the Cold War.

I cannot predict the outcome of that dangerous rivalry. The uncertainty is likely to stay. Where Singapore in Southeast Asia is concerned, I am one of many who have been concerned as to what those of Chinese origins might do when China calls on them as Chinese to sympathise with its aspirations for the future. Needless to say, there will also be repercussions in other Asean states. But no other state has a majority whose populace might be expected to provide a singular response to this inescapable dilemma.

Given Southeast Asia’s history of local cultures selecting what they needed from the civilisations they encountered, Singapore’s best interest seems to be to support the common aspirations of all member states of our region.

What it could do is to remind the new nation-states of their experiences with civilisations in the past, and the way they grew their local cultures by dealing with and learning from neighbouring civilisations. What they had chosen to learn were qualities that were borderless, those not identified with any national political system. Having done that for centuries, each Asean member had become confident in dealing with unpredictable conditions. In that way, each has been able to strengthen its local cultures and shape its own modern national culture. This was why the nation-states were able to come together and stay united as Asean when it was in their combined interests to do so.

Singapore as a state has chosen to stay with this common experience. It is committed to the idea that its citizens of whatever origin should respond only to borderless civilisational appeals and not to nationalist ones. At its simplest where China is concerned, it could distinguish between the current national culture and timeless Sinic civilisation. In Chinese, this would recognise a difference between zhongguo wenhua (中国文化) and zhonghua wenming (中华文明). China today has them both and may not think it necessary or important to project them separately. Singapore’s modern culture would require its leaders to try their hardest to keep the national and the civilisational clearly differentiated.

I do not want to give the impression that this would be easy to do. Careful judgments would have to be consistently made, and many cultural specialists would have to be involved to distinguish the two. But if successfully done, it should produce results that avoid any misunderstanding for all concerned.

The most important contribution of this differentiation is to ensure that Singaporeans of Chinese origin would be able to act in ways that the whole Asean community can understand and be comfortable with. That would show how a modern nation-state could, as with cultures in the past, coexist with a variety of living civilisations.

There is no question that all Asean states will closely observe how Singapore resolves its exceptional conundrum. The modernity with which the nation-states have identified should provide each of them with the capacity to deal with social plurality, although the scale of each manifestation is different.

Furthermore, if Singapore can sort out its problems with its citizenry and show how that response conforms to Southeast Asian experiences, it should strengthen the region’s confidence in responding to its relations with other civilisations. The region is fortunate to be one that is both maritime and continental, and also located strategically between two oceans that are vital to global prosperity. If it can hold firm as a united Asean that coexists with living civilisations, that might help to prevent our peace-seeking multi-civilisational world from descending into the warring nationalist cultures that threaten us today.

Source : SCMP